This week’s release of Uncharted 4: A Thief’s End on PS4 is a major event in the video game world. The fourth and final installment in the decade-long series, Uncharted is already being heralded as one of Sony’s most popular and successful games ever.

But the debut of Uncharted 4 is also important outside the world of video games because of its unabashed portrayal of masculine heroism in the figure of Nathan Drake, the game’s swashbuckling protagonist. As recently as a few years ago, it would have been dubious to give video game characters the same literary weight we usually reserve for characters in novels and films. But advances in technology have allowed game developers to create worlds as compelling as feature films and stories as labyrinthine as novels.

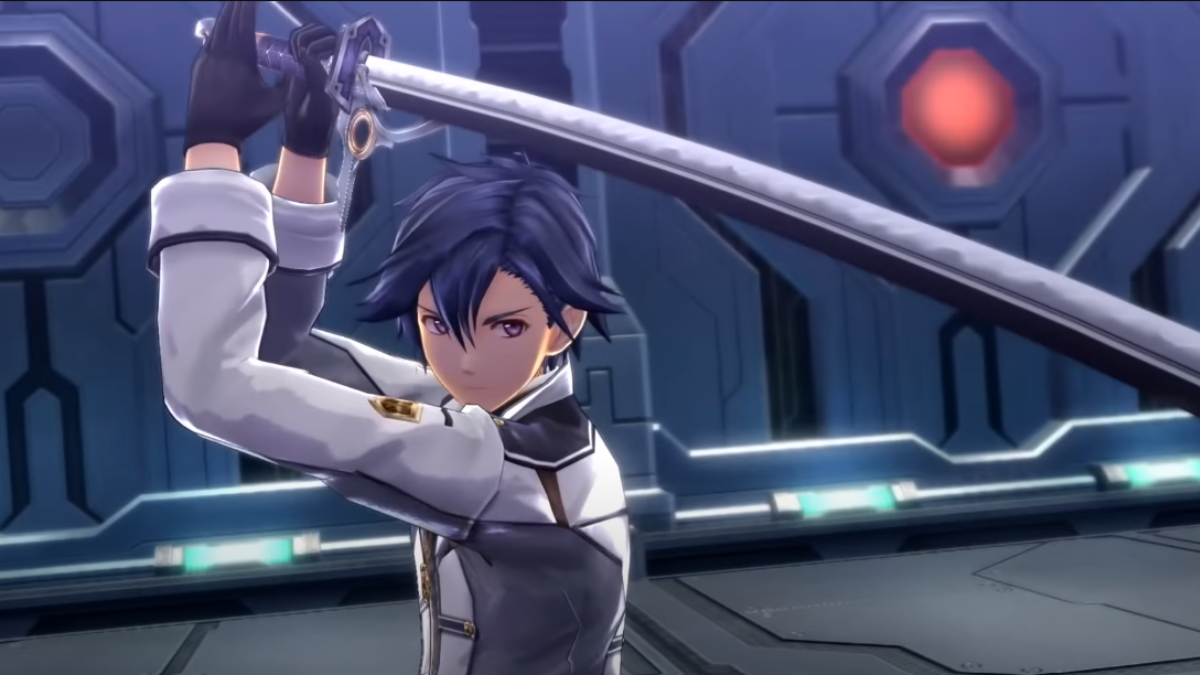

It’s also allowed them to create distinctive literary characters like Drake (voiced by the same actor in all four games, Nolan North), who is more or less a millennial Indiana Jones. He’s funny, self-deprecating, daring, reckless, and, at the end of the day, a man of principle. In our modern-day culture, what’s unique about Drake isn’t that he shoots bad guys or discovers lost cities. It’s that he’s a regular guy who believes in decency, loyalty, honor, courage, and love. He’s as old-fashioned as Humphrey Bogart’s Rick Blaine in Casablanca or Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe.

The Left’s War on Heroes

If you don’t think that’s a rarity these days, consider that the very concept of masculinity has come under fire in recent years from the Left. This headline, “America’s gun problem has everything to do with America’s masculinity problem” pretty sums up liberal thinking. Of course, it doesn’t take much to extrapolate this to politics. Republicans have a “masculinity problem”—a charge made all the more plausible, at least for liberals, with the rise of Donald Trump. Amid the current debate of transgender bathrooms and the broader trans agenda, one can find entire books about “Destructive Masculinity in Western Culture.”

One prominent symbol of both masculinity and old-fashioned patriotism, Captain America, has come in for special scrutiny. Vanity Fair laments the “heterosexual virility” of the new Captain America film, and criticizes it for taking away “the dream of Bucky and Cap” as gay lovers (as if that’s what most Captain America fans were holding out for). Salon thinks superheroes like Captain America and Thor are “setting unrealistic body standards for men.” And so on.

Superheroes are problematic for the Left, but so are regular old heroes—and even just ordinary men. Springfield College in Massachusetts, for instance, recently eliminated a course on “Men in Literature,” because it supposedly created a “hostile environment” for women. If men are a problem, then alpha males with twentieth-century attitudes about masculinity, morality, and honor are really a problem. These types tend to be both romantics and men of action, and none of them are what you would call domesticated or politically correct.

But they live by their principles, which often means sacrifice, giving up treasure or payment or reputation—the very objects of their adventures—in order to do what’s right. This is the constant fate, for example, of Captain Malcom Reynolds of the 2002 TV series “Firefly,” who always seems to give up his cargo or payment for the sake of his crew. And of course Indiana Jones never quite gets the artifacts back to the museum.

A more literary and moving example is Philip Marlowe, who rarely gets paid for uncovering the truth, constantly rejects the advances of women because sleeping with them wouldn’t be right under the circumstances, and not infrequently gets beat up for asking too many questions. At the end of The Long Goodbye he returns a $5,000 bill, saying, “Pick up your money, Señor Maioranos. It has too much blood on it.”

The Measure of a Man

As for Drake, in Uncharted he never seems to keep the treasures he finds. Uncharted 4 finds him leading the quiet life of a married man. Retired from treasure-hunting, he runs a salvage company and generally lives a life of peaceful, uneventful domestication. Without giving away the plot, Drake is jarred out of his staid life and thrust once more into a world of lost cities, ruthless villains, and treasure.

At first glance, this seems like a rebuke of the entire notion of domestication and martial bliss. But Drake’s wife Elena is herself an adventurer, an intrepid reporter Drake meets in the first Uncharted game and who accompanies him on some of his journeys. Just as Drake is modeled closely on Indiana Jones, Elena is a spitting image of Marion, Indiana’s erstwhile lover in Raiders of the Lost Ark, who saves her man more than once.

Like Indiana, Drake’s character constitutes a rebuke of the modern “beta male,” the cowardly man unwilling to stand up for his principles or defend the weak (or even move out of Mom and Dad’s house). If liberals thinks an alpha male is basically a sexist pig, conservatives point to Pajama Boy, the insufferable man-child of Obamacare, as the very embodiment of the beta male.

But lost in all this name-calling is a subtler reality about modern men: we’re aren’t binary, alpha males or beta males. The truth is that modern men are conflicted and often unsure how to navigate a culture that’s constantly telling us to suppress our masculinity and embrace our softer side—like that embarrassing New York Times listicle from last fall, “27 Ways to Be a Modern Man” (No. 20, “On occasion, the modern man is the little spoon. Some nights, when he is feeling down or vulnerable, he needs an emotional and physical shield.”).

The fact is, men should be manly. That doesn’t mean being sexist or bigoted, it means being willing to fight, physically if necessary, for what you believe. More than that, it means sticking by your principles, even at great personal cost. To quote the late, great Michael Kelly, there was a kind of American man of the 1930s and 40s—before Frank Sinatra and the invention of “cool”—exemplified by Bogart in Casablanca and Marlowe in The Long Goodbye, and also by Drake. That man, at his core, is a square:

He is willing to die for his beliefs, and his beliefs are, although he takes pains to hide it, old fashioned. He believes in truth, justice, the American way, and love… He is, after his fashion, a gentleman and, in a quite modern manner, a sexual egalitarian. He is forthright, contemptuous of dishonesty in all its forms, from posing to lying. He confronts his enemies openly and fairly, even if he might lose. He is honorable and virtuous, although he is properly suspicious of men who talk about honor and virtue. He may be world-weary, but he is not ironic.

If, in 2016, we need a video game character like Drake to convey this ideal of manliness to a new generation, then we’ll take a video game character.