“Father, this prayer is for everyone that feels they’re not good enough. This prayer’s for everybody who feels that they’re too messed up. For everyone who feels they’ve said ‘I’m sorry’ too many times…”

Those lyrics—spoken, not sung—raise the curtain on “Ultralight Prayer,” a brief Kanye West bonus track the rapper and producer dropped unexpectedly this past Easter Sunday. It’s not West himself who intones the invocation, but gospel superstar Kirk Franklin, jumping on the track to guest-star in the role of pastor.

Franklin’s sentiments are built on a similar, shorter prayer that he contributes at the dramatic finale of “Ultralight Beam,” a beautiful full-length track that leads Kanye’s latest album. The Easter version is basically just a short repackaging of one theme from its full-length cousin. But one important difference is impossible to miss.

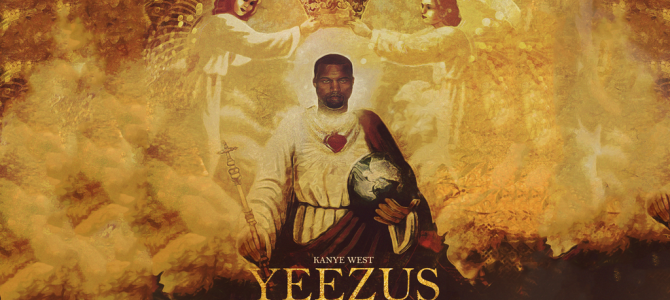

On the full-length version, the famously self-obsessed Kanye shares some of the spotlight with other artists—gospel singer Kelly Price, hip-hop wunderkind Chance the Rapper, and Franklin himself—but also keeps plenty of airtime for himself. When it comes to the even more religious remix, however, Kanye removes himself from the track entirely. No rapping, no singing, no faux prophecy from the man who once proclaimed himself “Yeezus.” The only voices left are Franklin, Price, and the gospel choir beneath them.

On Resurrection Day, apparently, even Yeezy can step out of the spotlight and let Jesus take center stage.

Questions About Kanye

Taken in isolation, “Ultralight Prayer” is pretty forgettable. It’s a two-minute eyeblink in Kanye’s vast catalog, which now spans more than a decade of music that ranges from angry and mournful and minimalistic to gleeful and lushly symphonic. But the little track acts as a signpost that points toward some of the most interesting questions we can ask about the polarizing producer.

How should Christian listeners view this man whose music sometimes genuinely strives for faith and other times treats Christian concepts as playthings? Does his erratic personal life foreclose any possibility of Christian witness? Is Kanye West a Christian artist?

The common, conventional response is either skepticism to outright scorn. After all, we’re talking about the megalomaniac mogul whose music frequently blasphemes and glorifies sin, whose behavior seems wildly out of control, and who famously seizes opportunities to run roughshod over others’ feelings in pursuit of self-gratification. In President Obama’s memorable analysis, “He’s a jackass.” With a rap sheet like this, who could take West seriously as a Christian artist?

Beauty Despite Brokenness

Especially for those of us who are conservative Christians, the easy course of action would be to weigh and measure West’s morals, find them wanting, and chuck him in the cultural compost bin. But this would be an error. If we fail to approach West in a spirit of charity and listen carefully to his tremendous music, it will be our loss.

That’s because, however objectively disappointing many of Yeezy’s personal choices may be, Christ’s teaching reminds us that grace can and does flow through all manner of human imperfections. His word shows that beautiful monuments to faith and love can indeed be built from the crooked timber of our fallen humanity.

I’ve argued before that conservatives should listen to hip-hop. Well, let’s extend that further: Christians should listen to Kanye West. To be sure, many of his offerings are vulgar or downright heretical. But some tracks gesture explicitly towards faith and yearn for the triumph of the eternal. Other songs, more like solemn soliloquies, stand up and witness to our fallen state, testifying to classic themes of Christian desolation, such as loneliness, solipsism, and damaging those we love most.

That’s my thesis. Any number of his songs could help me prove it. His latest album would require a post unto itself. For starters, let’s look at three older hits.

‘Jesus Walks’ (2004)

“Jesus Walks” was one of Kanye’s first massive blockbusters. It was one of several smash hit singles from “The College Dropout,” West’s first solo studio album. If the title didn’t make it obvious, this track brims with explicit Christianity. “We at war with terrorism, racism,” the introduction starts, “but most of all, we at war with ourselves.” Any believer can recognize the message: Facing down outside opposition can be a far clearer and easier task than staring down the demons in the mirror.

In a later verse, Kanye reminds his listeners that Christ’s church is a hospital for sinners: “To the hustlers, killers, murderers, drug dealers, even the strippers, Jesus walks for them. To the victims of welfare, for we livin’ in Hell here, hell yeah, Jesus walks for them!”

It’s hard to remember today, now that many of the most prominent hip-hop artists actively compete to convey social consciousness, but such grand philosophical statements weren’t the norm back when this record dropped. Part of the reason this record made such a splash is that we weren’t accustomed to hearing radio-friendly rap dive deeply and seriously into social, moral, and economic questions. For mainstream radio listeners, ethically serious rap that shone a clear spotlight on the trials and tribulations of urban America was a rare product in the early 2000s.

Then Kanye showed up. West describes this very dynamic in the closing verse of this anthem: “So here go my single, dog, radio needs this! They say you can rap about anything except for Jesus. That means guns, sex, lies, videotape – but if I talk about God, my record won’t get played?”

The Underdog and Alpha Dog Rolled Into One

To be sure, there’s a bit of a false victimization complex at play here. This song and album were immense commercial successes, and pretty obviously destined to be so. So it’s hard not to approach this supposed statement of nervous courage with skepticism. The lyric tastes a little bit like when a conversationalist tries to score cheap points by prefacing a totally acceptable, mainstream opinion with: “Now, I know this will be unpopular, but I’m gonna say it anyway!”

But even if “Jesus Walks” is a paradoxical effort to grab both mainstream acceptability and persecuted minority status at the same time—well, that’s a tension American Christians should be able to sympathize with!

For centuries, people who identified themselves as Christian constituted a powerful and dominant cultural majority in this country. Now that the tables are turning, we are quick to clamor for the kinds of institutional protections and carve-outs other minorities long sought to protect them from norms that were ostensibly ours. This is a tricky situation, reflected neatly in the irony of Kanye spending a bunch of airtime in one of his earliest smash hits pretending that it won’t be a hit.

It was a hit for good reason. The beat is catchy, the rapid-fire rhymes are impressive, and the repetitive chanting in the background is crazy compelling. In a final layer of interesting aural metaphor, it’s hard to decide whether that pulsing chant sounds more like a marching military platoon that needs to combat the world on Christ’s behalf or a gospel choir calmly celebrating a redemption that’s already assured. A song that can’t quite decide if it’s a battle hymn or a victory march offers a provocative reflection of our paradoxical Christian condition.

‘Only One’ (2014)

Fast-forward a decade, temporarily skipping over the bulk of Kanye’s work to date. We land on this bizarre little track that weirdly features Paul McCartney on keyboard. It was mostly panned by critics and fans alike and never even made it onto an album.

Like “Ultralight Beam,” Kanye released “Only One” as a holiday surprise, not on Easter Sunday, but New Year’s Eve. With my fellow Roman Catholics, I recognize that evening not just as a secular party, but as the vigil for the Solemnity of Mary, Mother of God—a special feast day that always occurs on January 1. Now, I’m not claiming that Yeezy grasped this liturgical detail, but the timing seemed fitting. Why?

Because “Only One” is a beautiful ode to maternity, specifically to Kanye’s mother, Donda West, who had died about seven years earlier. Some observers chalk up a lot of the searing self-doubt and public self-destructiveness that permeated West’s mid-career to the massive void she left in his life. He’s said publicly that he blames his lifestyle for her early death (which stemmed from plastic surgery complications).

But this peaceful track differs from the pained outbursts that preceded it. It’s not a rage against the night, but a mournful rumination on loss and a meditation on hope. Featuring auto-tuned singing to the exclusion of rapping, it’s basically the sonic version of a smile through tears.

“Only One” is structured as a message to Kanye from Donda in Heaven. Kanye is channeling words of wisdom that his mother would be offering him. The first verse, for example, offers a hopeful take on overcoming depression. “Hello ‘Mari,” Kanye sings as his mother to himself, “how ya doin’? I think the storm ran out of rain, the clouds are movin’.” Then a great line: “I know you’re happy, ‘cause I can see it. So tell the voice inside your head to believe it.”

‘You’re Not Perfect, But You’re Not Your Mistakes’

There is consolation and happiness here, but it isn’t a high-octane pep talk/battle cry hybrid like “Jesus Walks.” It’s peace through quiet prayer instead of cranking up the praise and worship. Each time the chorus loops around, it concludes this way: “Hello, my only one, remember who you are: No, you’re not perfect, but you’re not your mistakes.”

Talk about a concise summary of core Christian teaching. Our faith walks a unique line: We don’t deny or ignore human brokenness, but we refuse to give in to total despair. We aren’t perfect, but we are in fact redeemed. Both a profound, saddening awareness of our faults and the glorious knowledge of their expungement are essential parts of humanity’s story.

Kanye is obviously a broken guy. He swings wildly from one emotional extreme to the other; from unrepentant heresy, vain narcissism, and a chronic habit of committing the sin of scandal to earnest poetry about loving family and trying to worship God. But despite how dramatically he desperately needs to reform his ways, the persistence of his self-professed Christian faith helps remind us that God offers each of us myriad opportunities to correct our wrongs so long as we keep turning back to his mercy.

Who knows what’s written deepest on Yeezy’s heart? I don’t. But Kanye doesn’t have to have secured his own admittance to Heaven in order to help his listeners get there, and this one lyric might just prove a small asset. “You’re not perfect,” thanks to original sin and the tendency towards screwing up that it’s indelibly planted on each of us. But thanks to Christ’s sacrifice, it’s also true that “you’re not your mistakes.”

The first half of this truth falsifies the toxic modern lie that we can render ourselves morally blameless by neutering our own consciences. The second half falsifies pharisaism, mercilessness, and the easy myth that evil is unstoppable.

And apart from the song’s lyrical content, the very creative process to which Kanye attributes it recalls Christian praxis. He reportedly sought while writing the song to get his own ego out of the way and open a spiritual channel for his mother, making “Only One” the product of an attempt to silence the self rather than a triumphant feat of self-centered artistic willpower

Minimizing the personal ego to better channel higher and more beautiful things than we could ever produce on our own? That sure sounds like an attempt at deep prayer. Not bad for a throwaway bonus track. McCartney’s tranquil chords only sweeten the deal.

‘Runaway’ (2010)

So far, we’ve encountered a chippy anthem for marching in the light of God and a touching attempt to meditate on how motherly love might transcend death. But if we dip back into the albums that came between Kanye’s first hits and his most recent efforts, we’ll find more raw illustrations of heartbreak and human failure.

“Runaway” is one of the most distinctive tracks on “My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy,” the clear slam-dunk album in Kanye’s discography in terms of pure musical craftsmanship. It begins with a stark sequence of echoey, uncomfortably high-pitched notes on a slightly mistuned piano, before sliding into the kind of dense, lush, and painstakingly produced sonic tapestry that make the album so epic.

This song and album came before Kanye settled down with Kim Kardashian, before he had started his family. It was born of turmoil, not tranquility. According to the prevailing story about the album’s origins, West spawned it during a self-imposed exile after his infamous meltdown at Taylor Swift during the 2009 Video Music Awards and other similarly erratic behavior.

Nobody was sure what Yeezy was up to or what he was working through. It turned out he was working on an album. And one of its marquee songs was dedicated to his self-conception as a reverse King Midas who turns everything and everyone he touched into wreckage.

Kanye pours out his heart on this track. He laments his egotism and negativity, and wallows sorrowfully in his own sinfulness. “I always find, yeah, I always find something wrong,” West half-apologizes; “you been putting up with my shit just way too long. I’m so gifted at finding what I don’t like the most—so I think it’s time for us to have a toast.”

The “toast” he’s proposing is “for the d–chebags,” “the assholes,” “the scumbags,” and “the jerk-offs that’ll never take work off”—in other words, for himself. “Baby, I got a plan,” he advises the unnamed woman: “Run away as fast as you can.”

I Can’t Help My Sin

In an especially interesting turn, Kanye even expresses envy for the people he hurts: “I guess you’re at an advantage, ‘cause you can blame me for everything.” The victims of Kanye’s self-centeredness can just vilify him, move on, and heal; he’s the one who has to live with himself and his freakishly self-destructive impulses.

The message recalls the Bible’s Romans 7:19: “For I do not do the good I want, but I do the evil I do not want.” Indeed, to live any period of time as a serious Christian is to marvel at your own proclivity to screw up your own life and the lives of those around you. We’ve been given, we believe, clear instructions from God on how to live ethical and rightly ordered lives that will set us up to sow happiness, but we are unwilling or unable to adhere.

To be sure, few of us have screwed up as publicly or as dramatically as West has. But narcissism, egotism, romantic dysfunction, imperfect relationships with family? We might want to check our own eyes for planks before we scoff too judgmentally at the obvious flaws in Kanye’s personal life. While “Runaway’s” attempt at crafting a kind of profanity-laced secular psalm is spiritually imperfect, it might help create space for us to analyze our own personal tendencies, and to recognize mercy and goodness for the truly exogenous gifts that they are.

When we listen to “Runaway,” as when we listen to any of Kanye’s work, we should be careful to draw the right distinctions. I am certainly not suggesting that we overlook faults, minimize grave scandal or immorality, or regard even his overtly Christian efforts as fully earnest striving towards truth.

While West is deeply flawed and badly imperfect, however, he does seem to persist in trying to know Christ. This is certainly more than we can say for countless celebrities. To the extent that we join him in that common journey, we can listen to his beautiful music and hear echoes of a familiar oscillation between consolation and desolation, between overblown confidence and utter humiliation. And we can hear the twang of the tightrope that separates joy from despair.