Under normal circumstances, the Clinton and Trump tickets, along with down-ballot contenders, would by now be well into marketing wedge issues designed to sway voters. Those efforts have yet to begin in full force, however, given this Bizarro election world of pmurT.

At some point, though, the parties and candidates will begin to focus on particular issues. Given the recent media focus on the substantial price increase for the EpiPen, one likely emphasis will be the cost of prescription drugs.

While there are valid concerns about this issue, over the next three months watch out for five misguided attacks from both presidential candidates. They will likely push unwise policy proposals and tell the public that government intervention in the pharmaceutical industry is necessary. That would actually hurt sick people.

1. The Big Bad Bogeyman

Politicians and the media no longer need to resort to direct personal attacks. “Big” has become a stand-alone pejorative: Big Tobacco, Big Oil, Big Ag, Big Soda (I kid you not) and, when an industry catchphrase is too hard to craft, Big Business. So be prepared to hear a lot more about “Big Pharma.”

Of course, “Big” tells us nothing about the problem or best solutions. But this narrative powerfully juxtaposes Big (i.e. Bad) Pharma with sick and suffering individuals. It will be difficult, if not impossible, for the industry to change the narrative after Martin Shkreli—former chief executive officer of Turing Pharmaceuticals—increased, overnight, the price of Daraprim, a medicine used by cancer and AIDS patients, from $13.50 to $750 a pop.

Since then, Shkreli has been indicted for securities fraud, further casting aspersions on the industry. Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, a representative of drug company interests, has tried to distance itself from Shkreli. These efforts have proven futile, though, because not since Imelda Marcos’s shoes danced across our television screen in the 1980s has there been a more visceral image of greed.

Since Shkreli emerged as Big Pharma’s bogeyman, Big Pharma has been roundly castigated. The day after the New York Times reported on Turing’s 4,000 percent overnight price increase for Daraprim, Hillary Clinton tweeted:

Donald Trump also joined the fray, as The Hill reported, calling Shkreli a “spoiled brat.”

Shkreli continues to be the media’s go-to bad boy: CBS News trotted him out to comment on the EpiPen controversy. Much to its (presumed) dismay, Mylan, the manufacturer of the EpiPen, now finds itself involuntarily tethered to Shkreli.

Pitting Big Pharma against the small sick guy obscures the real adversaries to Big Pharma: Big Insurance and Big Government. In the United States, individual patients do not pay the high price for these drugs: private insurance companies and taxpayers do (through Medicare and Medicaid). Money drives their decisions as much as it does Big Pharma.

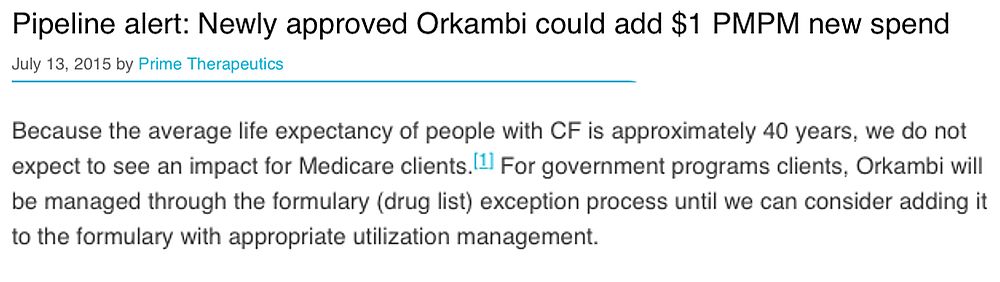

For instance, before settling with three Medicaid patients last year, Arkansas denied three cystic fibrosis patients access to Vertex’s breakthrough $311,000-a-year drug Kalydeco. The Wall Street Journal reported: “Emails obtained by the patients’ attorneys show officials discussing Kalydeco’s cost, and their worries about the expense of future cystic fibrosis drugs.” More unsettling, perhaps, was the way Prime Therapeutics, a prescription drug manager and mail order pharmacy, originally framed its discussion of Vertex’s follow-up cystic fibrosis drug, Orkambi:

In other words, Prime Therapeutics told its Medicare clients not to worry about the expense because the people who would benefit from this pricey drug will die long before they are eligible for Medicare! Prime Therapeutics apparently realized broadcasting this morbid outlook might not sync with its professed mission of “helping people get the medicine they need to feel better and live well,” and it has since deleted the above language I captured by screenshot.

Yet the health insurance industry, through The Campaign for Sustainable Rx Pricing, casts itself as the noble knight and Big Pharma as no different than the evil Shkreli.

So every time you hear “Big Pharma,” remember the opposite side of that coin is “Big Insurance” and not the individual patient, even though politicians like to portray their concern as being for individual Americans facing “extreme costs.”

2. The Grass Is Always Greener

A second talking point focuses on the lower prices paid for prescription drugs in other countries. For example, Clinton’s campaign highlights the perceived inequity, writing: “it’s unfair that drug companies charge far lower prices abroad for the same treatment, while imposing higher prices on Americans. Countries in Europe often pay half of what Americans pay for the same drugs.” The recent outcry over the cost of the EpiPen mimics this talking point, with MoveOn.Org noting in the background for its “Stop Immoral Price Gouging for Life-Saving EpiPen” petition that an EpiPen “two-pack is just $85 in France.”

While drug companies do charge lower prices in Europe and even far lower ones in Africa, pharmaceutical firms must price their drugs based on the political, social, and economic conditions of those countries. It is invalid to compare prices based on price controls and (in Africa) charity with U.S. pricing.

Further, the lower prices in those countries come at a cost: delayed access and rationing. For instance, cystic fibrosis patients in the United States had access to Kalydeco since its approval in January 2012, while the first European Union country to authorize reimbursement, the United Kingdom, delayed coverage until December 2012. Australian patients faced a longer wait, with coverage approved in December 2014, and Canadian patients were delayed until June 2014.

Both Clinton and Trump contend the price disparity can be eliminated if consumers can import cheaper drugs. Clinton proposes to “allow Americans to safely and securely import drugs for personal use from foreign nations whose safety standards are as strong as those in the United States.” Trump offered a similar idea during the March Republican debates in Florida, as summarized by John Graham at Forbes.com:

Trump’s “Health Care Reform to Make America Great Again,” reiterates that approach.

This “solution” has been floated for over a decade. More than ten years ago, when Congress was considering similar legislation, Doug Bandow explained many of the problems of such an approach, including that pharmaceutical companies could refuse to supply pharmacies that reimport to the United States, or foreign countries would lose access to drugs to avoid reimportation.

More recently, John Graham laid out the devastating effect reimportation would have on intellectual property protections, and in turn innovation. However, the biggest negative will be the danger to consumers over counterfeit drugs. While Clinton and Trump both profess that only safe imports would be allowed, as Roger Bates explained in “The High Cost of Cheaper Drugs,” “[p]harmaceutical companies are better positioned to source and import drugs than patients are: they have experience, expertise, and reputations to maintain.” While reimportation sounds a simple and attractive solution, the costs are too high.

It is an unfortunate reality that drugs are priced in the United States to “subsidize the rest of the industrial world,” where incomes are lower and price controls are the norm. But none of the current proposals will address the inequity of the situation, and could make the situation worse. Most Americans also do not want to trade lower drug prices for price controls, delayed access, and rationing.

3. Neglected R&D

Critics also justify government interference in the pharmaceutical sector by arguing that high drug prices are not the result of investments in R&D and are thus suspect. Clinton takes this tack in selling her proposals. She first notes that “new drugs can constitute incredible breakthroughs in treating disease … and we need to ensure that there are proper incentives for real innovation.”

But then Clinton seeks “to require pharmaceutical companies that benefit from federal support to invest a sufficient amount of their revenue in R&D.” She also proposes restrictions on direct-to-consumer advertising. However, neither proposal impacts the price of pharmaceuticals. Instead, these proposals micro-manage pharmaceutical companies to create the illusion that the government is doing something to address drug prices.

Avik Roy recently zeroed in on Gilead, the pharmaceutical company responsible for the blockbuster hepatitis drug Sovalid. Roy noted that Gilead “charged unprecedented sums” for the hepatitis drug, even though it had not discovered the drug. Roy implies Gilead reaped a windfall because it had merely purchased Pharmasset, which had discovered Sovalid, and had not expended R&D money itself. To imply a windfall, though, ignores that Gilead compensated Pharmasset for the R&D it had already expended.

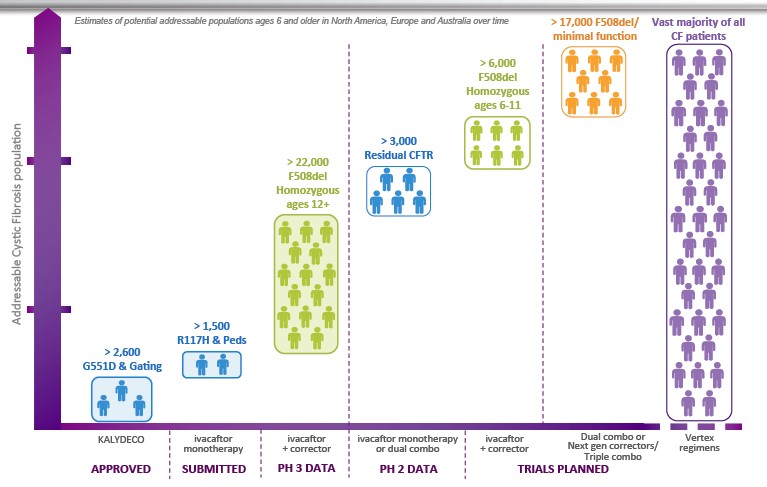

Further, while politicians and policy advisors express concern over drug prices based on the purported lack of R&D expenditures, even when funds are reinvested in R&D critics abound. For instance, with proceeds from Kalydeco and Orkambi sales, Vertex invested heavily in additional R&D for cystic fibrosis, including next-generation drugs that could reach more than the small percentage (about 10 percent) of cystic fibrosis patients who benefit from Kalydeco. Yet, even understanding this dynamic, David Orenstein, co-director of the Palumbo Cystic Fibrosis Center, “felt strongly that the price represented a major escalation in the problem of soaring drug costs.”

Similarly, when the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation sold its rights to royalties from the Vertex drugs for $3.3 billion (yes, billion with a “B”), it saw itself subject to unnerving scrutiny even though CFF invested much of that money in additional research. Thus, the neglected R&D argument seems a pretext under which to attack the sticker price, so it does not justify interfering with internal decisions about R&D expenditures, advertising, and other management prerogatives.

4. Drugs Versus Doctors

A fourth focal point for attacks on Big Pharma is the increasing amount of money spent on drugs compared with other health-care spending. During the primaries, Clinton focused on this point in a television advertisement entitled “Doubled.” In that ad, her campaign lamented: “Heart disease. Asthma. Diabetes. Seven out of 10 Americans take prescription drugs. But in the last seven years drug prices have doubled.”

However, as FactCheck.org explains: “That’s inaccurate. A report, provided by her campaign, says brand-name drug prices on average have more than doubled. But more than 80 percent of filled prescriptions are generic drugs, and those prices have declined by nearly 63 percent, that same report says.” FactCheck.org adds that “the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services says in its latest National Health Expenditure report that the shift to cheaper generic drugs has resulted in ‘historically low rates of prescription drug spending growth’ in recent years.”

Roy, though, finds the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ statistics misleading. He points out that “American spending on prescription drugs looks quite manageable, representing 10% of national health expenditures. That would appear to compare favorably to hospital spending, at 32%.” Roy, however, argues “those numbers are an illusion,” because when hospitals dispense medication, it is tallied as hospital spending—not drug spending.

Likewise, a physician administering intravenous drugs “is counted as physician spending, not drug spending.” Roy claims when those figures are included, “drug spending skyrockets to 17% of overall expenditures,” and may be as high as 20 percent of total U.S. health-care spending. He concludes: “Americans today spend one of every five to six healthcare dollars on prescription drugs—a share that continues to rise…”

Two responses: First, even if drug expenditures total 17 percent of overall medical expenditures, the centers’ conclusion that the shift to generic drugs resulted in historically low rates of drug spending growth remains valid because it scored the various expenditures consistently from year to year. Thus, contrary to the impression conveyed by Clinton’s misleading “Doubling” ad, things are getting better, not worse.

Second, notwithstanding Roy’s portrayal of too much relative spending on drugs as a negative, an increase in drug expenditures relative to doctor and hospital expenses might well be a positive. For instance, a vaccine for Zika or Ebola would both increase drug spending and simultaneously decrease costs spent on doctors and hospitalizations, and together it would have a synergistic impact on the percentage of health-care spending on prescription drugs. But that would be a great thing, not something to lament.

Also, even if such vaccines debuted with a high price tag, once the shift to generic drugs occurs, the long-term cost will decrease substantially, while doctor and hospital costs (which escalate over time) will be avoided. Thus, it is wrong to act as if money spent on drugs is money that would be better spent on doctors or other areas of health care.

5. The Missing Market

A final rationale offered to justify government interference in prescription drug pricing focuses on the distortions of the pharmaceutical market. Roy stressed this point, bluntly writing: “We don’t have a free market for prescription drugs in the U.S.” He explains: “Most drug companies have the luxury of pricing their products however they want, because a fourth party (employers or the government) is paying a third party (insurers) to pay a second party (the manufacturer).”

This analysis, however, assumes there are no substitute drugs, which is rarely the case. Insurance companies have long used formularies to identify covered brands or generic equivalents. Absent inclusion on a formulary, drug manufacturers lack access to a segment of customers. As Dr. Steven Miller, chief medical officer of Express Scripts (the largest pharmacy benefits manager), explained to the New York Times: “With exclusions, bidding to get on the formulary becomes more of a winner-take-all contest. The winning companies gain more market share because rivals are excluded, so they are ‘willing to give us greater discounts.’”

Thus, far from having free rein with pricing, pharmaceutical companies must negotiate a fair price with the insurance company or lose market share.

Admittedly, these competitive forces do not exist for drugs possessing market exclusivity. Clinton homes in on this market deficiency to justify her plan to address drug costs, writing that often specialty “drugs are the only ones on the market—and with no competition to keep the price down, drug companies can charge excessive prices.” But while imperfect, market forces are still at work: The high price of the drugs incentivizes other pharmaceutical companies to enter the market.

Vertex’s $311,000 cystic fibrosis drug Kalydeco is a case study in the market forces at play. The New Yorker and Discover Magazine have excellent articles detailing the long history of this drug, the development of which dates back to 1998 by a small San Diego biotech company, Aurora Biosciences. At that time, the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation provided funding for the initial research because, as former CEO Bob Beall explained:

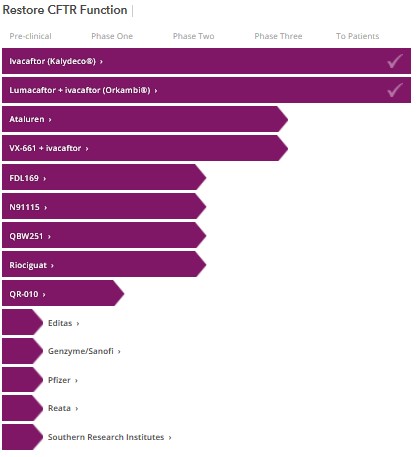

But even with funding from CFF, Beall had difficulty attracting pharmaceutical companies. He had contacted five that specialized in high-throughput screening (a new technique then that could quickly screen chemical compounds for potential development), but only two returned his calls, one of which was Aurora Biosciences. However, now at least ten companies are researching mechanisms to restore the function of the Cystic Fibrosis gene (called the CFTR), including some of the big names: Pfizer and Bayer.

This increased competition will result in better drugs and, over time, lower prices. In the interim, the high price for such breakthrough therapies is not a bug of the system, it is a feature: the potential high return encourages investment in pharmaceuticals.

Can A Drug Price Be Too High?

None of this is to say that a drug can never be overpriced. “A Tale of Two Drugs,” by Barry Werth, explored this issue by comparing the vastly different cases of two high-priced drugs: Kalydeco (then $307,000) and Zaltrap ($132,000). Werth’s narrative makes clear that Zaltrap was overpriced—a conclusion its manufacturer impliedly conceded by cutting the price in half within months of the launch. (The market drove this reduction, as doctors refused to prescribe the drug.) For anyone serious about drug pricing and looking for something more than platitudes, “A Tale of Two Drugs” is worth a read.

“A Tale of Two Drugs” shows it is difficult to assess when a drug is priced too high. That difficulty stems from many factors, in part from an uncertainty concerning the real cost of the drugs because of rebates, coupons, and discounts. It also is not easy to determine the total costs pharmaceutical companies incur in developing drugs. While it is possible to calculate the cost of pre-trial and clinical trial development for a specific drug, the percentage of drugs that make it through development is small, and companies must recoup enough on the drugs that reach the market to pay for the ones that don’t.

Then the question arises: what is a fair return on investment in the high-risk environment of pharmaceuticals? (This question is antithetical to our governing economic system.) Further, in assessing a “fair” price for a drug, the benefits must be considered, including the savings resulting from other health-care expenditures rendered unnecessary; lost productivity (by both the patient and family members); and of course, the physical, mental, and emotional well-being of the patient and his family.

In assessing the savings, too, a farsighted approach is needed because today’s expensive drugs will be tomorrow’s generic drugs, and those cheaper drugs will continue to reduce future medical expenses. Yet in discussing the high price of drugs, these points are rarely mentioned by the politicians or those pushing to rein in Big Pharma. Instead, you’ll hear some version of the scare tactics highlighted above.

Likewise, the public often has a purely visceral response to drugs’ sticker price. Telling in this regard was a comment David Orenstein, co-director of the Palumbo Cystic Fibrosis Center at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, made to Werth. After the price of Kalydeco was disclosed, Dr. Orenstein relayed: “I think everybody just went, ‘Whoa, that doesn’t seem right.’” Orenstein, who took a lead role in discussing the price with Vertex’s CEO, Jeff Leiden, also shared a worry:

[W]hen he first wrote Leiden about Kalydeco, he worried what would happen if Leiden said to him ‘Okay, you’ve convinced me. What would be a better price?’ Orenstein concedes he doesn’t know.

Unfortunately, the “Whoa, that doesn’t seem right” response is typical in the discussion of drug prices, as illustrated when Beall sat down with Diane Reime. Her disgust over the price for Kalydeco was evident in her questioning. Yet no one pointed out that Vertex, which was founded in 1989, reported an annual net profit only once. So if Vertex has only once been profitable during its nearly 30-year existence, but $311,000 is too much to charge for this lifesaving drug, what is the appropriate price? That is the tough question for which no one seems to have a response, and for which government is least suited to answer.

What Do We Do About High Drug Prices?

So does that mean we ignore drugs’ high price? Here, I agree with Roy that conservatives shouldn’t ignore this issue because they oppose price controls. But politicians and policy makers should not demonize Big Pharma (which, after all, creates the cures for so many sick and suffering individuals), fantasize about unattainable prices fixed in other countries, pretend mandated reinvestment in R&D will solve the problem, or fixate on the price tag. Rather, government should come at the problem from a different angle: instead of focusing on price, use innovation as the yardstick.

The Innovation Yardstick

Rather than price, the focus should be on the number of new and improved pharmaceuticals the FDA has approved. While the pharmaceutical market is imperfect, the government plays an important role in establishing an optimally functioning market—one that rewards innovation and risk, while assuring competition regulates pricing.

Government does this by creating temporary monopolies through patents and exclusivity periods. The important thing is to achieve the right balance. If a monopoly lasts too long, prices will remain too high for too long; if the monopolistic period is too short, pharmaceutical companies will not invest in new drugs.

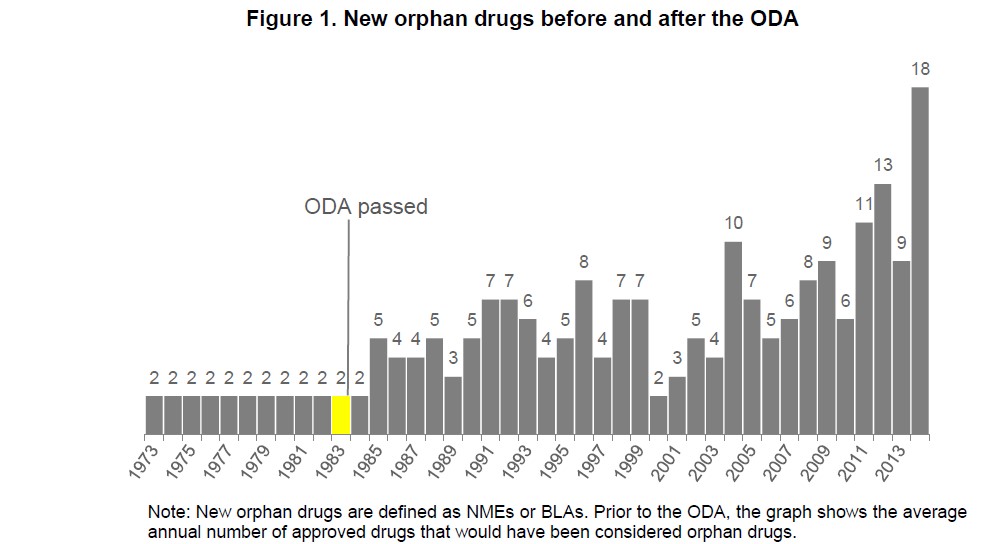

The government’s influence in this area is readily seen in orphan drugs and summarized in this white paper. Orphan drugs treat “orphan diseases”—ones so rare that pharmaceutical companies would not “adopt” them without financial incentives. Prior to passage of the Orphan Drug Act in 1983, which encouraged investment in rare disease or conditions by, among other things, providing tax breaks and an extended exclusivity period, the FDA approved only 34 new orphan drugs. Since then, the FDA has approved more than 200 new orphan drugs.

The increased innovation resulting from the Orphan Drug Act demonstrates the government’s power to adjust the market where it does not function optimally. Likewise, the government, by reducing exclusivity protection, thereby allowing generic drugs to reach consumers sooner, could provide a mechanism to lower drug costs. Jon Hartley suggests a similar approach in his recent National Review article.

But any such reduction should happen slowly—beginning with a one-year reduction in grants of market exclusivity. If investments and innovations decline, Congress will know more financial incentive is necessary to produce treatments and cures. But if the rate of FDA approvals continues unabated, a further reduction could be implemented.

Now, theoretically, reducing the exclusivity period could result in price increases because pharmaceutical companies must recoup their investment over a shorter time period, but if the number of pharmaceutical trials remains stable or increases, competition will help prevent this outcome. Congress should also consider authorizing the FDA to provide differing exclusivity periods based on the gaps in drug research. This would allow the FDA to encourage the development of drugs for which there are few or no current treatments, such as Lou Gehrig’s disease, while allowing generics to reach the market sooner if adequate substitute drugs exist.

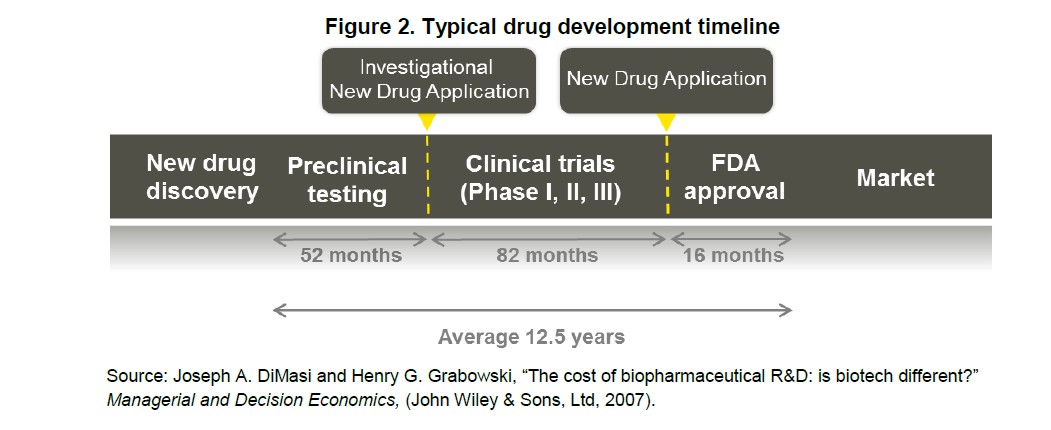

The pharmaceutical sector will likely fight any decrease in exclusivity periods. But there is good reason reducing it may be appropriate: Congress established exclusivity periods prior to the breathtaking advancements in high throughput screening. Since the 1990s, when Aurora Biosciences used this robotic process to discover the compound that would later become Kalydeco, high-throughput screening “has become universal within the Pharmaceutical and Biotech industries as the major approach to identify novel prototype molecules for new targets.” The ability to quickly and accurately test chemical compounds speeds up the drug discovery process and increases the chance that drug benefits seen in vitro will translate into clinical benefits and later FDA approval. As the timeline needed for trials bends from the historical 12.5 years average, extended exclusivity periods should no longer be necessary.

However, Hillary Clinton’s suggestion that the exclusivity period for biologics be reduced from 12 years to 7 years goes too far too quickly. We do not want to put the brakes on research, and prudence dictates moving cautiously to assess how the market adjusts.

The Shkrelis of the world will always be with us, but policy makers should ignore the soundbites and bogeyman and focus on the desired outcome: new innovative drugs.

Disclosures: As the mother of a young son with cystic fibrosis, Cleveland has a vested interest in the continued development of drugs to treat and eventually cure this disease. Her family’s 401(k) and retirement savings include diverse holdings, including mutual funds in both the health care and pharmaceutical sectors; it also includes immaterial investments in several individual biotech stocks, including Vertex.