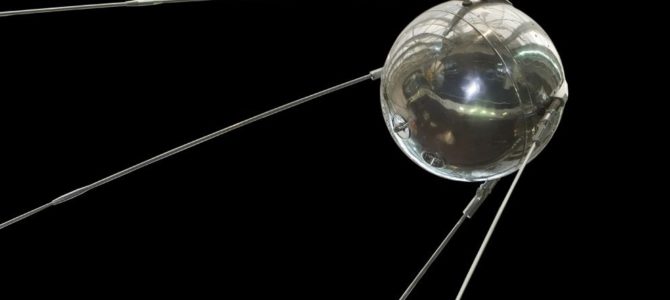

Sixty years ago today, the Soviet Union astounded the world by launching a spherical radio weighing 185 pounds to circumvent the globe every 96 minutes. A three-stage R-7 “semyorka” (ol’ number seven) lifted “Sputnik”—the first artificial satellite—into low-earth orbit, and variants of this launch vehicle remain in operation today including manned Soyuz missions.

Sputnik’s onboard transmitters broadcast for three weeks, enabling amateur radio operators to monitor the satellite until its batteries expired. The mute sentinel continued to course the heavens until atmospheric drag caused its reentry three months following its launch and four weeks before the Americans successfully launched their first satellite, Explorer-1.

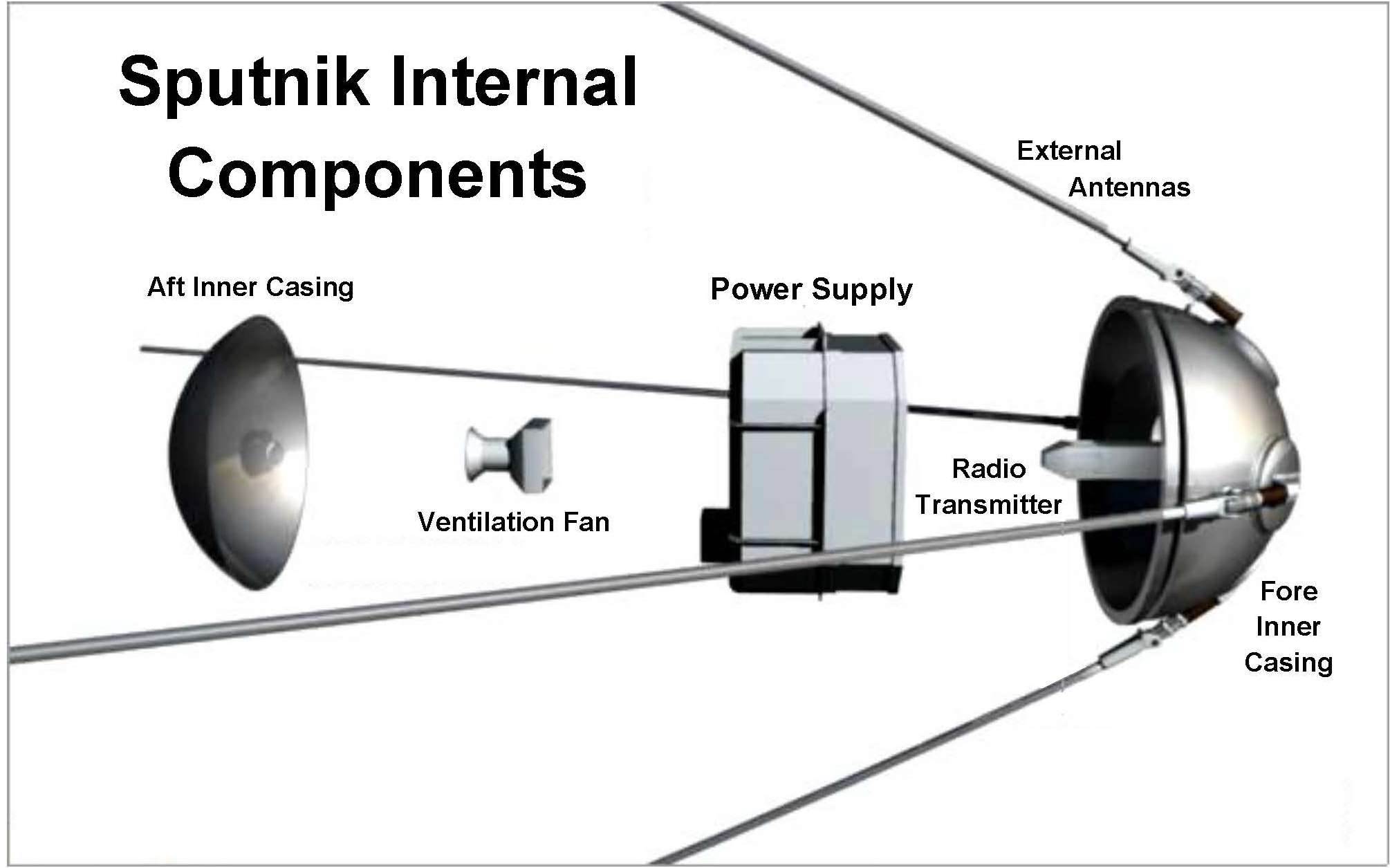

Sputnik’s casing housed a comparatively unsophisticated package. The inner fore casing held four antennas extending aft from the round shell, as well as a pair of radio transmitters broadcasting pulses at 20 megahertz (high frequency) and 40 megahertz (very high frequency or VHF). A power supply from triple silver-zinc batteries and a ventilation fan nestled between the inner fore and aft casings.

The Man Who Designed Sputnik

Credit for Sputnik’s historic achievement belongs primarily to the “Chief Designer” Sergei Korolev (1907-1966). Premier Nikita Khrushchev shrouded his name in secrecy, along with design characteristics of the R-7 rocket and even its launch location—Baikonur cosmodrome near Tyuratam in Kazakhstan. A stocky man with an intense demeanor, Korolev spent long hours in project management, paying meticulous attention to detail. Graduating from Bauman Moscow State Technical University in July 1926, he worked in aviation and earned a pilot’s license in 1930 before undertaking rockets the succeeding year.

After his arrest in 1936 along with engineering colleagues, he was tortured at Lubyanka prison and sent to a Kolyma gold mine, where he lost most of his teeth from scurvy before being returned to Moscow in late 1939 to serve in a sharashka penitentiary for the educated until his release in 1944. During the Second World War, his group designed bombers and rocket-assisted take-off boosters for aircraft. The paranoid nature of Soviet society discouraged Korolev from discussing his incarceration, which had severely damaged his health.

Commissioned into the Red Army as a colonel in 1945, he reviewed German V2 rocket technology, and began developing long-range ballistic missiles as a priority from Joseph Stalin. Beginning with a replica of the V2 designated R-1 first tested in 1947, Korolev’s team proceeded to design and build larger rockets leading to the intermediate range ballistic missile (IRBM) and later the intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), of which the R-7 became the first.

After several failures, the R-7 successfully flew 3,700 miles to the eastern edge of Russia six weeks before Sputnik launched. The liquid-oxygen (LOX) and kerosene burning R-7 included a core with a four-chambered RD-108 engine (yielding 92 tons thrust at sea level thrust) accompanied by four strap-on boosters each equipped with a four-chambered RD-107 rocket engine (yielding 83 tons thrust at sea level). The ICBM version reached 112 feet tall and weighed 310 tons fully loaded after being horizontally transported and elevated to vertical at the launch pad. The Sputnik launcher was slightly shorter at 95 feet in height.

Initially designed to carry a six-ton thermonuclear warhead with an explosive yield of three megatons of TNT (200 times more powerful than “Little Boy” at Hiroshima) across a distance of 5,500 miles, the R-7 was eventually deemed impractical for this purpose, but instead became the foundation for launching payloads into orbit.

R-7 variants lifted manned Vostok and Voskhod spacecraft into orbit during Korolev’s lifetime. Eight years after Sputnik, Korolev died from medical complications while undergoing surgery. Josh Gelernter provides a thumbnail sketch of the chief designer in National Review. Fifteen months later, the Soviet space program suffered the loss of Korolev’s guidance in the fatal mission of Soyuz-1.

Sputnik Launched A Thousand Grimaces

Sputnik had profound effects on America’s political psyche—anxiety bordering on hysteria over public science education and military preparedness. These days, one might wonder what all the fuss was about. Popular historical literature describes the 1950s as economically optimistic and internationally paranoid as industrial countries either exploited consumer demand or were rebuilding the infrastructure destroyed during the Second World War.

Meanwhile, political firebrands exploited fears of Soviet hegemony in eastern Europe and Sino blandishments along the Pacific rim (with memories fresh only four years after cease-fire on the Korean peninsula). The period from the late 1940s through the early 1960s also exhibited rapid technical progress in the aerospace and electronics industries when aircraft and circuit controls improved in speed and power with introduction of jet engines and solid-state semiconductors. And, of course, rockets.

Public dismay in the United States over Sputnik did not concern an oversize beeper, but rather the evident technical capacity of the atheistic oligarchs in the Kremlin to rain death and destruction on our heads with little or no warning. American vulnerability to a devastating attack from an expansive secretive country widely presumed to operate on near-subsistence level raised the specter of another sudden attack within living memory of Pearl Harbor. This assessment of alleged inadequacy became reinforced after less than a month when the Soviets launched Sputnik-2. Its massive payload weighed nearly eight tons, including a dog and its life support, signifying the size of warhead that could be directed our way.

Clearly, this second satellite alarmingly demonstrated that the Soviets had, through intense technological emphasis, devised the capability of hurling massive nuclear warheads across the globe by ICBMs, not to mention neighboring allies by IRBMs. Thus, if the masters of a Slavic slave society could surreptitiously leapfrog our proud accomplishments, just how susceptible would North America or Europe be to a first strike? The logistical difficulties in preparing such launchers propelled by kerosene and cryogenic LOX, as well as targeting guidance, were then only poorly understood except by specialists. Minimal knowledge was accessible to the public, so media speculation and political grandstanding fueled the hysteria.

Exploiting Public Hysteria for Political Gain

The panic among Americans in the wake of Sputnik, exacerbated by hyperventilating congressional critics regarding the administration’s delicate balancing of defensive security while preserving economic integrity, perplexed President Eisenhower. Although keen to prevent a surprise attack like Pearl Harbor, Eisenhower was hobbled by the paucity of publicly available information on an ideological adversary that obscured its comparative risk exposure to America’s strategic bomber squadrons. By investing in technology over the course of his two terms, Eisenhower sought to avoid both a garrison state and fiscal insolvency by creating retaliatory sufficiency while preserving limited government.

Meanwhile, Senate Democrats, notably former Air Force secretary Stuart Symington and majority leader Lyndon Johnson, sought to erode the popular former general’s political support (and distract from their party’s segregation policies in the South) with demands for accelerated development, exploiting the public’s understandable ignorance of the numerous classified programs underway. This propensity to expand centralized control continues, as echoed by “never to let a serious crisis go to waste” in the memorable words of Rahm Emanuel more than five decades later.

As described by historian Walter McDougall in his seminal “…The Heavens and the Earth,” Eisenhower had three major reasons for not elevating satellite launches a priority. First, orbiting a satellite was already an objective for America’s participation in the International Geophysical Year (IGY) from July 1957 to December 1958 under the civilian Vanguard program. Second, missile research was proceeding apace, so emergency measures were unnecessary. Third, given Soviet secrecy to preclude intelligence verification, freedom of orbital space remained untested prior to Sputnik.

Project Vanguard, funded by the National Science Foundation for IGY research and managed by the Naval Research Laboratory, could not directly benefit from the Air Force or Army technology due to their classified nature. The month after Sputnik-2, a publicized Vanguard rocket erupted into a fireball at launch, to much humiliation. The following March, Vanguard succeeded with a three-pound satellite that still remains in orbit.

Americans Work Feverishly to Compete

As a complement to our long-range jet bombers, the Army, Air Force, and Navy labored quietly in the 1950s to design and build intermediate range and intercontinental ballistic missiles, and progress was proceeding apace without expensive rushing. The Air Force advanced in succession and concurrently: Atlas (ICBM), Thor (IRBM), and Titan (ICBM), all becoming the heritage basis for satellite launchers.

The Army invested its access to German V2 rocket technology (the “V” an abbreviation for “Vergeltungswaffen,” meaning vengeance weapon) into IRBMs such as Redstone and Jupiter. The Navy, reluctant to adopt liquid propellants for ship-board integration, embarked on Polaris equipped with solid rocket motors. In September 1956, an Army’s Jupiter-C successfully completed a sub-orbital ballistic flight that might have attained orbit with an upper stage. Only after Vanguard’s failure did another Jupiter-C launch Explorer-1 in late January 1958.

Earlier in December 1955, Eisenhower proposed “Open Skies” to mutually verify military installations, seeking to defuse tensions with the Soviet Union while desiring information on its offensive capabilities to better calibrate retaliative preparedness without excess waste or inviting weakness. Khrushchev’s abrupt dismissal indicated Soviet intent to shroud limitations in technological and industrial ability to project power.

In his memoirs, Eisenhower describes his efforts and ultimate disappointment from Moscow’s rejection. Because of the closed nature of communist society and the extensive territorial expanse within which Russia could conceal laboratories and production facilities, Eisenhower embarked on aerial reconnaissance, including the high-altitude U-2 jet glider for flight photography over Soviet airspace. However, such operations would provoke Soviet attempts to down such aircraft and thus constituted a temporary expedient.

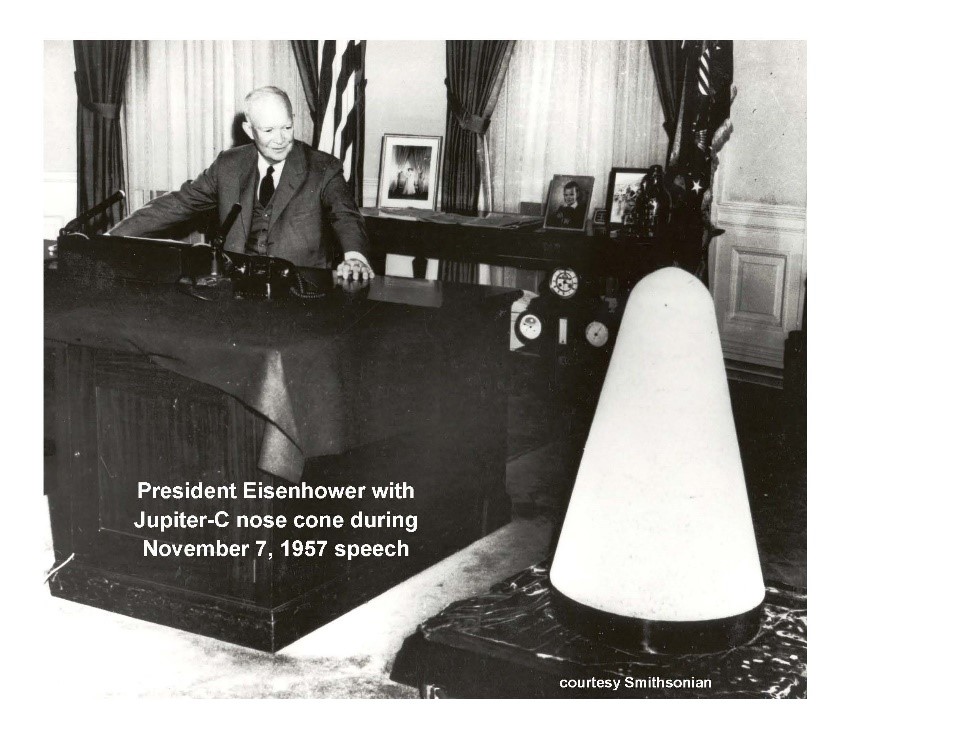

Hence, Eisenhower also directed teams to create reconnaissance satellites to photograph installations from orbit, with the film recovered and processed after satellite reentry and retrieval. The technical issues presented significant engineering challenges, some of which were released for the Discoverer satellites such as re-entry, but the objectives mostly disguised under the name Corona. Less than a week after Sputnik-2, Eisenhower displayed a Jupiter-C nosecone during a televised address at the White House. Anxiety remained about potential Soviet protest of orbiting satellites overhead, unless the Russians eliminated the problem by initiating the first satellite themselves. Tactically, deferral of an American satellite obviated this concern, but at the cost of national anxiety over an unexpected technological coup.

Sputnik’s Long-Term Repercussions

Agreement between congressional and administration leaders on civilian participation in space endeavors led to the creation of the National Air and Space Administration (NASA) in July 1958. The political reaction to Sputnik also catalyzed federal encroachment into public schools. In September 1958, President Eisenhower signed the National Defense Education Act (NDEA) to provide funding for seven years to promote secondary mathematics and science curricula and rescind the post-war “life adjustment” emphasis then in vogue.

Later, the National Education Association argued against the elitist focus on technology in preference of broader measures to diminish attention on “gifted” students. Congress amended the NDEA in 1964 to delete the cynosure on science and mathematics, while maintaining federal involvement in local education.

Russia continues its projects in orbit and beyond, including further improvements of the Soyuz spacecraft under development during Korolev’s directorship. The latest variant Soyuz-MS spacecraft currently ferries cosmonauts and astronauts on the Soyuz-FG launcher to the International Space Station, which includes Russian modules Zvezda, Zaria, Pirs, Poisk and Rassvet, with later add-ons Nauka and Uzlovoy.

Not only does the retirement of America’s Space Shuttle program necessitate contracts with Russia for manned entry into earth orbit aboard Soyuz, astronauts prospectively aboard Boeing CST-100 capsules will be launched on the Atlas-V, which incorporates Russian RD-180 engines. Such are the ironies looking back on past Cold War rivalries.

Sputnik provides a turning point in world history: from then on, humans would maintain a presence in outer space and begin reaching to the stars, although haltingly. The emergency response that its launch sparked eventually subsided, while the technological legacy spawned from that milieu to go faster and higher, albeit muted in the public arena, continues to this day.