Jacobo Comin (1518-1594) has always been a controversial artist. Born the son of a “tintore”, or “cloth dyer” in Venice, as a boy he was briefly apprenticed to the painter Titian (c.1488-1576), but was sent home after about a week and a half for reasons that remain unclear: either the budding young artist was already too talented to be trained, or he was too difficult to control, or both.

His neighborhood nickname of “Tintoretto,” which he adopted and used in honor of his father’s trade, may be the one by which he is commonly known today, but the one that many of his contemporaries used to refer to him, “Il Furioso,” he earned thanks to a bold personality and a highly driven work ethic that, combined with his raw talent, changed the history of Western art.

As the new National Gallery of Art exhibition “Tintoretto: Artist of Renaissance Venice” aptly demonstrates in the first major exhibition of his work ever held in the United States, Tintoretto’s rebellious and boundless energy was successfully channeled into a long, productive career. From altarpieces and devotional pictures, to portraits and mythological scenes, he tried his hand at painting just about everything, and this show provides ample examples of his work in all of these genres.

His personal goal, which he allegedly painted on the wall of his studio, was to combine the draughtsmanship of Michelangelo with the painting skill of his disapproving former master (and later rival), Titian. Yet as it unfolds, the NGA’s exhibition demonstrates how Tintoretto managed to add something uniquely his own to this fusion of the dominant artistic styles of Tuscany and Venice.

A Personality Like a Peppercorn

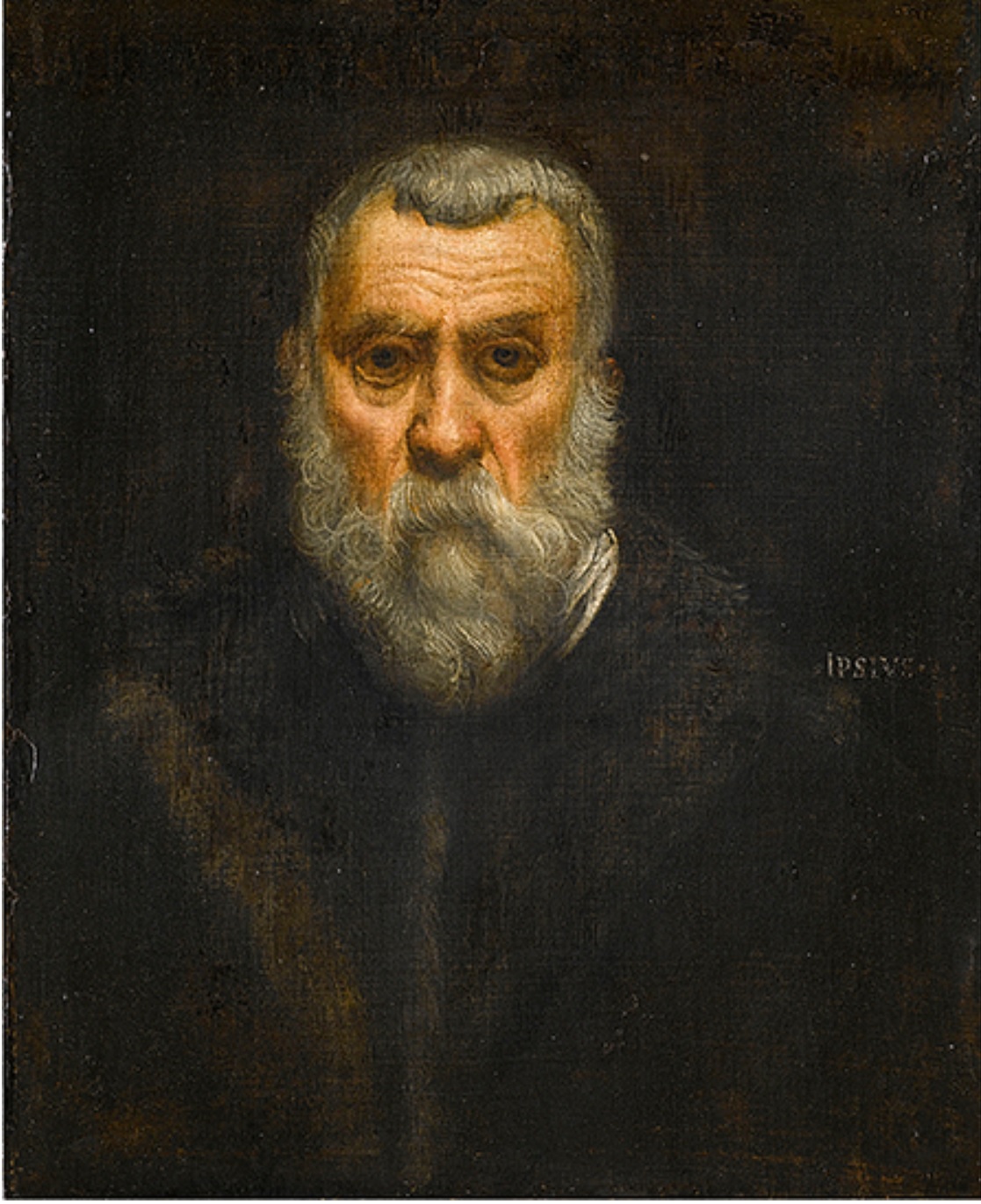

The show begins and ends with two self-portraits by the artist, whom a fellow Venetian described as being small in size but with a dominating personality, like a peppercorn. The first portrait, painted in about 1546 and on loan from the Philadelphia Museum of Art, depicts the young Tintoretto with a mass of curly hair and a scraggly beard, staring out at us with a challenging, audacious look in his large eyes.

That same intensity characterizes his second self-portrait from 1588, lent by the Louvre for this exhibition, but now Tintoretto is shown as an elderly, successful man with receding white hair, a groomed beard, and a luxurious fur coat. If the first self-portrait looks something like a contemporary hipster or professional protestor, the second is strangely reminiscent of an establishment icon like Andrew Carnegie.

Between the execution of these two private works, Tintoretto managed to throw into public chaos previously held concepts of what the art of painting ought to be. Long before the Impressionists, Tintoretto began to experiment with different techniques for quickly painting oil on canvas, attempting to permanently capture that movement the human eye only perceives in a passing instant.

The longer he painted, the looser and freer Tintoretto’s brushwork became, and the deeper his contrasts of light and shadow. The result is that when you compare an earlier picture in the NGA exhibition, such as the museum’s own “Conversion of Saint Paul” (c. 1544), painted when Tintoretto was a young, up-and-coming artist, to a mature work such as his “Flagellation of Christ” from the late 1570s on loan from Prague Castle, you could be forgiven for thinking that these two canvases were executed by two completely different artists.

The “Conversion” demonstrates the lessons Tintoretto learned from the often lower-status painters who were employed to decorate household objects such as dowry chests or library tables. They had to work quickly, with an economy of line and bright colors that allowed their compositions to be understood at a distance. Tintoretto’s tumult of muscular figures scattering in all directions, as Saul falls from his horse on the way to Damascus, demonstrates both his study of Michelangelo’s sculptures and Titian’s paintings, but could just as easily have been painted onto the surface of a Renaissance majolica serving platter as onto canvas.

Decades later, the contrast between the raking light of a torch—a light source that is suggested, but not actually shown in the picture—and the deep shadows of Tintoretto’s haunting night scene of the “Flagellation” is almost cinematic. It underscores not only Tintoretto’s significant development as an artist in the roughly 30 years that had passed since the “Conversion,” but also anticipates by several centuries the aesthetics sought by filmmakers like the German Expressionists, and later by American and French film noir directors.

The viewer cringes in anticipation of the blow about to be struck by the guard holding the whip, as he winds up for his next strike, and the seemingly disembodied, booted leg behind the bound figure of Jesus provides an unsettling note. No wonder that Jean-Paul Sartre referred to Tintoretto as history’s first film director.

Go Big, Go Bold, and Stay Home

Because he painted so quickly and tirelessly, Tintoretto could turn out more work in a month than other painters could in a year. This facility, combined with his loose brushwork, led to criticism that many of his paintings looked unfinished.

While our 21st century eyes are quite accustomed to the idea of an image being formed by skillful combinations of light and dark paint, or by juxtaposing more finished and more sketchy areas of a picture, in 16th century Italy the notion that one could suggest a facial feature, a bit of drapery, or a flower with just a deft flick of the brush was a radical one. In the end, Tintoretto’s exceptional speed in conceptualizing, preparing for, and executing his work allowed him to plunge with great gusto into the challenges posed by commissions of exceptionally large size.

One of the challenges with mounting an exhibition of Tintoretto’s work is that so many of his paintings are too large to be moved: many simply cannot be squeezed into the cargo hold of existing aircraft, or even safely transported across the Venetian lagoons from the churches and palaces where they normally reside.

Consider Tintoretto’s “Il Paradiso” (“The Paradise”), generally considered to be the largest Old Master painting in existence, and possibly the largest work on canvas ever painted, which stretches nearly 75 feet across and 30 feet high. The picture hangs, as it has since its completion, behind the throne of the Doge, the elected leader of the Venetian Republic. Understandably, this colossal work is not a part of the National Gallery exhibition, but Tintoretto’s final concept painting for it is, and it’s quite large.

On loan from the Thyssen-Bornemizsa in Madrid, Tintoretto’s ginormous preparatory study for “Il Paradiso” is roughly 16 feet long, and 5 1/2 feet tall. It was painted by the master himself in about 1588, while the full-scale work in the Doge’s Palace was executed by Tintoretto and his studio assistants between 1588 and 1592.

With its masses of swirling clouds and enormous numbers of saintly and angelic figures interacting with one another, there’s so much going on that many exhibition visitors on opening day appeared to be completely overwhelmed by it. Yet large as it is, this isn’t even the largest painting in the NGA show.

That title belongs to the “Madonna dei Tesorieri” (“Madonna of the Treasurers”), painted circa 1567 and on loan from the Accademia in Venice. Beautifully set off in the exhibition design by the rich blue walls and white carved moldings that surround it, the canvas is a whopping 17 feet across and seven feet high, and depicts the three Venetian treasury officials who commissioned the painting, accompanied by their assistants. All are coming in adoration before the Madonna and Child, who are then surrounded by several saints. If I were to choose a single work in this exhibition as best-encompassing everything that makes a Tintoretto a Tintoretto, it might well be this extraordinary piece.

The painting shows off the artist’s skill in composition and drawing, and his unique brushwork: note how the twisting figure of the Christ Child, shaded by the body of the Virgin Mary, looks more like a sketch than a finished element of the picture. It also demonstrates Tintoretto’s love of dramatic effects, as well as his very Venetian use of intensely saturated color contrasted with neutrals and deep blacks.

Gorgeously Saturated Colors and Textures

There’s a wonderful passage around the hands of the central figure, in which the light bouncing off the satin of the deep crimson gown is suggested by squiggled brushwork executed in an unexpected combination of indigo and sky blue with white highlights. Seen up close, the juxtaposition of colors makes no logical sense; seen at a distance, everything combines perfectly.

The official robes of the other two city officials, made of red velvet lined with ermine fur, appear wonderfully plush and almost tactile, thanks to Tintoretto’s expert handling of paint dragged across canvas to create pools of color. Notice also how the skies over the rolling hills and distant mountains of the background are being obscured by gathering storm clouds, again, executed in a variety of contrasting colors that come together to suggest optical perception rather than concrete reality. One wonders whether the unsettled weather intentionally portends the increasing tensions at the time between the Venetian Republic and the Ottoman Empire, culminating in the famous Battle of Lepanto, which took place only three years after this picture was painted.

Tintoretto was also highly interested in creating somewhat theatrical architectural settings in his work, as this painting demonstrates perfectly. The viewer’s eye is drawn out across an enormous, patterned marble floor, which ends suddenly and with no obvious transition into the natural landscape beyond.

The location for this encounter between the civic and the sacred appears to be the terrace of an idealized palazzo sited in the Veneto, the countryside on the Venetian mainland, a location likely not chosen at random. At the same time Tintoretto was painting this picture, the great Venetian architect Andrea Palladio (1508-1580) was building his famous classical villas such as “La Rotunda” in the Veneto, giving rise to the Palladian architectural style that went on to influence later generations of architects from Sir Christopher Wren to Thomas Jefferson to Robert Venturi.

In this single work, Tintoretto manages to demonstrate his astonishing artistic skill, while simultaneously evoking the wealth and power of the Venetian Republic, the piety of its citizens, the grandeur of its architecture, the natural beauty of its countryside, its resolution against threats from without, and of course, the self-confidence of Venetian artists, architects, and designers: no small feat, that.

A Genius With a Lack of Finish

The question of the artistic legacy stemming from works like these was debated even during Tintoretto’s own lifetime. His contemporary, the artist, architect, and historian Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574), recognized that Tintoretto was a genius of the first order. He found Tintoretto “swift, resolute, fantastic, and extravagant, and the most extraordinary brain that the art of painting has ever produced.”

At the same time however, like many other 16th century observers, Vasari criticized what was perceived as a lack of finish in Tintoretto’s work. Vasari whinged that “if only [Tintoretto] had recognized how great an advantage he had from nature, and had improved it by reasonable study, as has been done by those who have followed the beautiful manners of his predecessors, and had not dashed his work off by mere skill of hand, he would have been one of the greatest painters that Venice has ever had.” The irony of course, is that today few people can name a single painting by Vasari, whereas Tintoretto is considered not only one of the greatest of all Venetian painters, but also one of the greatest of all Old Master painters, period.

Although logistics will always conspire to prevent the majority of Tintoretto’s greatest paintings from ever leaving Venice, there is perhaps something rather appropriate about that limitation on viewing his work. As the most Venetian of all the Venetian Renaissance painters, and something of a hothead to boot, Tintoretto demands that you go to Venice to see his paintings where he intended you to see them. If that proves to be impossible for you any time soon, then be assured that the National Gallery’s new exhibition is your next best bet.

If you can’t get enough Tintoretto from this exhibition, however, don’t worry: the National Gallery has plenty more on offer. The NGA is also holding two additional exhibitions touching on the master’s work and times. “Drawing in Tintoretto’s Venice” features a number of drawings by the artist, rare survivors all, as well as drawings by his son, assistants, and rivals. There’s even a selection of drawings that may have been executed by El Greco (1541-1614), who studied in Venice as a young artist before moving to Rome and then on to Spain.

A third exhibition as part of the Tintoretto celebrations at the NGA is, “Venetian Prints in the Time of Tintoretto,” showing printed works that Tintoretto and his workshop would have been familiar with as they circulated among 16th century artists. There’s also an excellent documentary film, produced by the National Gallery and narrated by actor Stanley Tucci, that provides an overview of Tintoretto’s life and work. You can stream it on the National Gallery’s YouTube channel.

“Tintoretto: Artist of Renaissance Venice,” is at the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC through July 7, 2019. “Drawing in Tintoretto’s Venice” and “Venetian Prints in the Time of Tintoretto” continue at the National Gallery through June 9, 2019.