In a deep dive this week, The Wall Street Journal compiled many of the familiar grievances of America’s luckiest generation. “Playing Catch-Up in the Game of Life,” reads the headline. “Millennials Approach Middle Age in Crisis: New data show they’re in worse financial shape than every preceding living generation and may never recover.”

Like most articles of this genre, the Journal fails to stress that most millennial tribulations—and, really, sweeping statements about any arbitrary generational grouping is a ham-fisted way to talk about people—are largely driven by the choices it makes rather than a sorry state of our politics, economy, or science, which, as I write here, favors younger people in every quantifiable way.

The WSJ article, for instance, notes that millennial households “had an average net worth of about $92,000 in 2016, nearly 40% less than Gen X households in 2001, adjusted for inflation, and about 20% less than baby boomer households in 1989.”

The driving reason for this disparity is the millennial penchant for delaying traditional adult milestones. As a group, they are prone to choose short-term happiness and independence over long-term wealth accumulation. Now, maybe millennials are leading more fulfilling lives than their parents and grandparents, and maybe not. Comparing themselves economically to generations that embraced a different set of priorities at the same age, and then wondering why the results are different, however, is disingenuous.

For example, millennials should consider themselves lucky that college is more readily available to them (this includes the poor) than any previous generation. Yet, you don’t have to rack up hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt by going to expensive schools. But the tradeoff for a higher education is often more debt, and delayed wealth.

College is too expensive for a host of reasons. There is no utopia. Yet, in the years before the government injected moral hazard into the equation by backing loans for every useless journalism degree, both lender and borrower had to weigh the compromises of debt. Perhaps being a well-read and well-rounded person with a fine arts degree is more important to you than an engineering degree and a big paycheck. That’s fine. That’s a choice.

Psychology, the seventh-most popular major in the United States, is also the 160th most useful major in making a living. Humanities degrees, honorable as they might be, are the least useful degrees for making a good living. They are also, by far, the most popular majors in colleges today. Then again, only around 27 percent of college graduates find jobs related to their majors.

If there were a healthy, properly incentivized economic structure in higher education, banks wouldn’t be handing out loans to students without any thought to their future earning potential. There isn’t.

Also, millennials aren’t compelled to rent apartments in the middle of the most expensive cities in America. Yet, many are happier living in urban areas than previous generations were. Pew Research found in 2018 that 88 percent of millennials now reside in metropolitan areas. That’s also a choice.

And the urban areas that millennials choose are more expensive partly because they are far better iterations of cities than previous generations encountered. In the past 30 years, these places have undergone waves of gentrification and revival, in part to cater to the tastes of younger Americans. Most are cleaner, safer, and more livable in numerous ways—and thus, more pricey. Yes, Brooklyn was a lot cheaper in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. It was also more dangerous, dirtier, and less enticing for families and businesses.

So are suburbs. Buying a house, it’s frequently pointed out, can be prohibitively expensive. It’s also true that those houses are better when compared to the houses millennials’ parents and grandparents grew up in. The average square footage of a non-air conditioned, light-deprived, and poorly insulated home in 1950 was 983 square feet. In 1970 it was 1,500 square feet. In 1990, it was 2,080. And in 2014 it was 2,657 square feet. If you live in the suburbs, you probably live in a veritable castle.

Despite the perception, these castles are often within reach. The growth of the upper middle class—something we rarely hear about—has skewed the national average of home ownership. Yes, the median home value in Montgomery County, Md. is $451,600. In Nassau County, New York it’s $542,700. And in Arlington, Va., it’s $689,300.

These are unaffordable for someone starting out. But the median price of a three-bedroom home in Des Moines, Iowa is $139,500. In Fort Worth, $197,500. In Charlotte, it’s $225,500. Most millennial tragedy pieces focus on young people in major metropolitan areas like New York, Chicago, and DC, but there are plenty of reasonable options in the hinterlands of Georgia, Minnesota, and New Mexico.

Some millennials are now starting to move to cheaper cities and older millennials are starting to embrace the same patterns of movement toward the suburbs as other generations have. But they’re doing so at an older age, and after years of paying rent and taking on debt rather than saving for new homes. The later you start, the later you amass wealth.

One way to delay conventional adult milestones is by staying single. Perhaps the fact that millennials will live longer and heathier lives, and remain more active in their later years, generates less urgency about marriage. But, the fact is, married couples are wealthier. Much wealthier.

Studies show that Americans who get and stayed married “double the wealth of single people who never married. Together, the couple’s wealth was four times that of a single person’s.” Some of this is attributable to the fact that successful people tend to get and stay married in the first place. Yet there are numerous other factors involved.

Although The Wall Street Journal offered an example of a rare couple who (possibly) benefited from delaying marriage because of loan rates, most couples can take advantage of economies of scale, pooling their savings, work, resources, intellectual ability, and leaning on the stability of family life to succeed. According to Pew, 65 percent of boomers were married by the age of 37, and 57 percent of Gen-Xers. Only 46 percent of millennials will be.

Millennials also like to argue that, other than electronic trinkets (what some of us refer to as mind-blowing miracles of technology, entertainment, and information-sharing), everything is more expensive. This isn’t true.

The price of goods and services dictated largely by the marketplace (because of trade, enhanced productivity, technology, and competition) have become more affordable for millennials. Goods and services that have seen enhanced government interference, on the other hand, have become more expensive. Even among those items—take health care—costs are commensurate with the huge technological advances medicine has made to enhance the lives of average Americans.

Every generation has lived through recessions (in fact, we’re lucky that we haven’t had another one yet). Many of those downturns inflicted far more tangible damage to the everyday lives of Americans than the recession of 2007. The rush to transform 2007 into the biggest tragedy of American history was largely driven by political reasons. Now it’s used as a crutch to explain the alleged unique hardships of an entire generation.

Here’s is how the Journal article describes it.

Hobbled by the financial crisis and recession that struck as they began their working life, Americans born between 1981 and 1996 have failed to match every other generation of young adults born since the Great Depression.

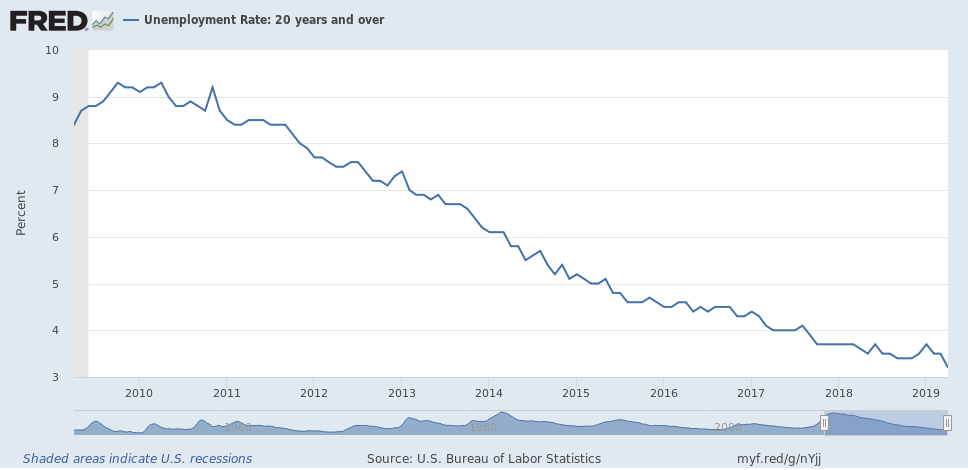

Of course, there is a lot more to a good economy, but the unemployment rate peaked at 10 percent in Oct. 2010 before taking a downward trajectory. In 1982, the average unemployment rate for the entire year was 9.7 percent, on average. In 1983, it was 9.6.

By the end, the decades of the 2000s and 2010s will have had average unemployment rates on par, or better, than in the ’70s, ’80s and ’90s. For young millennials, this is what the unemployment rate looks like since they began their working life:

If a young millennial began working during the Obama administration, he would have, at worst, seen four quarters of negative growth.

source: tradingeconomics.com

Of course life has a new set of challenges for every generation, and no one expects millennials to sit around prefacing every complaint by noting, “Hey, life is better for me in so many ways.” But it’s simply untrue, despite a sense of unearned victimhood, that millennials have it harder than those who came before them. In most ways, the opposite is true.